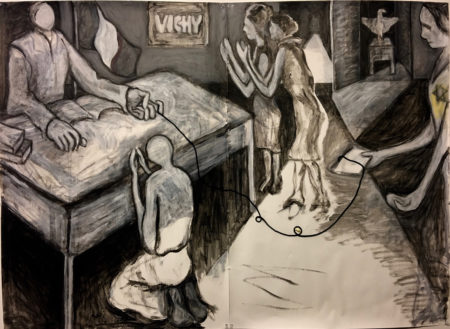

Ceija Stojka, The Women of Revensbrück

Ceija Stojka, Deportation in an Extermination Camp

The residency in Paris continues… it also keeps improving, which is hard to imagine, since it has been so gratifying all along. I sit with two artists who are drawing my portrait. One is from Serbia and the other from Iran, and we talk about politics and religion and our beliefs and of course, art. That night I go for dinner with an Iraqi artist and we also talk about our way of seeing the world, religion and art and being women. I go to French class and we talk about how each of us thinks about life and art and culture and meaning, and we are from Finland, and Iceland, and Austria, and Germany, and Egypt and Japan and yes, the U.S.

I do my work – write, paint, but I also live Paris. I take myself to a French film, La Douleur, based on Marguerite Duras’ diaries. I read the book years ago – it’s about the War. A German filmmaker here is making a film about Duras’ husband and has seen La Douleur, and we go out for drinks and yak about it. I am superbly engaged and grateful for this world where every street and many people have something current going on about the past. Oh yes, there are digital art fairs, le monde numérique and the Pompidou and the Palais de Tokyo have moved way past the times I am still living, but I am not alone here.

A few days later I am on a walk in the Marais and par hasard (perhaps my favorite French expression, followed closely by formidable!), I stop by a gallery and am floored by the exhibit. It’s the work of a self-taught Rom, gypsy, artist, Ceija Stojka, and includes many amazingly profound paintings and drawings of her childhood in Auschwitz, Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen camps. Some of it is breathtaking and reminds me of Munch and Kollwitz, two artists I revere. Stojka started painting at age 50 or so, and when I watch a film at the exhibit about her experience and life, I see her take gobs of paint into her hands, both hands, and then smear it over the cardboard canvas. The drawings are haunting… ghostlike figures, wisps of cloud, barracks, rifles, whips, but also les tournesols, sunflowers, in a field after the Liberation. Suffering and life beyond. She talks about becoming close to the bodies at Bergen Belsen for warmth and protection… the entrails had been eaten, so all that was left were piles and piles of skeletons and skin. I am riveted, just like when I first saw the amazing paintings of Charlotte Salomon and others who recorded their experience of those years. Knock out. I tell my friends here at the Cité and one knows Stojka’s work and wrote an article about her… Yes.

My connection to my own history is visceral here in Paris. When I discover photos or info in various archives about my family or parents, I experience an unfamiliar sense of belonging. The night after I saw La Douleur, which I found somewhat sentimentalized and too intensely dramatized for my taste, given the subject matter… who had really suffered in that tale? Was it truly the person waiting for news or the person imprisoned at Buchenwald and Dachau? But I digress – after the film I was walking home and noticing the people in the restaurants late at night, lovers at the table by the window, a group laughing at the pizzeria, smokers sitting outside at the sidewalk café under those lamps pumping heat into the frigid air, and suddenly I felt that I was my mother, in her body, walking these same streets before the War. A frisson of otherworldly visitation. And when another day, at the archives in Seine-Saint-Denis, I happened across three tiny ancient photos of my father in the Spanish Civil War, I looked at his face, shaded by a military hat, and saw myself.

I came to France to make art and write, but an unexpected byproduct, an outgrowth of the process perhaps, is that I have unearthed, or maybe the more accurate description would be, I have stumbled upon a lineage, roots, and a permanent sense of place. It is here. I am of here.