I’ve been painting images for a graphic book. I don’t know if it’s a graphic novel truly — that label evokes something like comics or cartoons, as they call it in France. But whatever this compilation of imagery might be named, it’s made up of eighty or so paintings. Some are oils on paper, one or two are on canvas, and many are acrylics on paper.

What I want to pay attention to here is that I find certain images stand out as most compelling. Overall, the paintings depict characters and scenes. They are light in subject matter or heavy, bright colors or black and white. A few are very quiet and only have minimal action; many are busy and loud.

But what calls to me is intensity. Intensity of feeling, of color, of stroke, of line, of story. There’s one image called The Empty Bed where a woman sits curled on a chair, head on knees, next to a bed covered with crumpled covers and a lonely pack of cigarettes. Someone has left town.

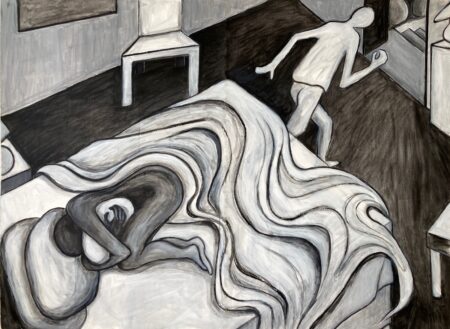

Or there’s the one I just completed called Abandoned where another woman lies curled in the fetal position on a bed as a man gallops out the open doorway.

Not all intense images are of domestic psychological drama. There’s the one of two Jews hiding at the Paris train station at the start of WWII —

or the one of a grown daughter catching her frail mother as she starts to fall.

It’s not as though the more forceful paintings are inherently more skillful or esthetically pleasing than the rest. No, it’s that they manage to reveal visually what has been up until that moment simply an internal state.

How does that come about? There is something we feel, it can be a matter of emotion or memory or idea, which then calls for a possible visual conceptualization. Like take the intimation of abandonment — maybe it starts with a kind of discomfort in the chest or stomach or even the head… a buzz or tightness or alert signal, perhaps familiar, harkening back to early loss or experience. Then let’s say the person sensing the discomfort wants to translate that perception into a tangible, material, expression. It could be written about, or spoken about. But in this case, the person, I, want to describe it visually.

And here’s the magic part. I ask myself, What does this experience look like? And just like that, a scene pops into my head. Oh, I think. There is a woman lying on a bed and someone is leaving her behind. Now where did that come from? Is it happening in that moment to me? Usually not. Did it once occur? Did I read it in a book? Did I see it in a painting? Maybe. But maybe not. Sometimes it seems to just emerge as I sketch, sort of like how writers describe a character starting to tell the writer the story rather than the other way around. For me I might start with — Here’s a beach. There is a palm tree and a sky and sand. Then I might just go ahead and paint that. The next morning while I’m meditating I realize there wants to be a woman and her old mother standing on the beach, and the younger woman is pointing at the beauty, and the old woman starts to transform into a bird flying in the sky.

Okay, I say. That’s cool. And while I’m adding the two women and start on the woman becoming a bird, I think Chagall. Did I see this image in a Chagall painting when I went to that museum on the Côte d’Azur six years ago while at that artist colony, La Napoule? I look up Chagall, and sure enough he has everyone flying around in the sky.

The point I want to make is this. Something seems to happen in life where suddenly a strong, deep and amorphous experience is transformed into something concrete and material and external. It becomes art. To me that seems unbelievable. I heard an artist tell the story of attending a concert and then deciding to create paintings for each movement of the composition she heard. She later went to meet the composer and brought her paintings. There were eight of them for the eight movements. Before she said anything, the composer pointed out which painting was a visual expression of each movement. He saw his work translated into visual symbolism and immediately recognized it.

Could that happen with non-intense communications? I don’t know. Am I simply pulled to intensity because of my cultural heritage, my personal history, my biology, my gender? Whatever the underlying reason, what I am taken by is the thrill of the process. Emotion leads to a desire to express visually, which leads to a kind of dream state, which leads to an image coming to mind. The image is put on paper or into music, or into a dance or a story and the artist says, Yes! That is exactly it. And she puts down her paintbrush and goes and pours herself a gin Martini. As Georgia O’Keefe is supposed to have said, Any day when I work is a good day. Maybe I would say, any day when it works is a good day.