It’s all about the fires right now in L.A. They started a week ago, well, actually a week ago and two days. And there really is no space to be distracted by anything else.

Last Tuesday when I looked down the beach and noticed the first smoke wafting up from what looked like downtown Santa Monica, it didn’t seem like much. But by that night, I already knew that this was too close, too big, too crazy for me to brush off. The news warned that the Santa Ana winds were revving up to a predicted 90-100 MPH. Winds that would whip through the already much too dry brush from months of drought, common in this Southern California desert-like climate. Conclusion: any spark, from an electric line, from a cigarette, from anything hot, could burst into flames.

And some already had, it would appear. Up the coast in the Pacific Palisades. I could see the mounting smoke sitting over the ocean in the view out my apartment window, the red lights of fire engines racing up and down the hills across the water. Around 5PM, the sun set between the streaks of black soot in the sky, and it was eerily beautiful. I kept checking my New York Times app, the source with the best maps: the fire was moving south, towards our part of town. People were being evacuated, and I started thinking about it having something to do with me.

Watching news reports in the NYT is one thing. Sad, upsetting. But not personal. However, this was getting closer and closer to an event that might actually impinge on my very privileged and easy life. No, my life hasn’t always been easy, and I often joke that I paid my dues or paid at the office, apologetically suggesting that it was a hard road until it wasn’t. And that’s true. But now in retirement, and living on the water in Santa Monica, I was having the life of Riley, or whatever metaphor one might use for good fortune bestowed on someone who has made her way out of the trenches. I’m not talking money here, but rather the wish to live close to the ocean, to be able to see a sunset out my window, to be enveloped in mother nature.

But Tuesday night, January 7th, it didn’t feel like ease to me. How would I know if we were supposed to evacuate? Does someone call? My partner went down to the front desk of our building and asked if the perennial false fire alarm would be activated when there really was a fire to warn residents of the many apartments in the high-rise we called home. Not surprisingly, the person on duty didn’t really know.

I decided to stay awake or at least keep waking up to check my phone. And to leave it on in case there was some sort of mindreading genie who would notify us that we were in the path of the flames. And as hoped, I managed to wake every hour or two and check the news. Would that have saved me if the fire had decided to turn its attention in this direction? Nope… since waking an hour after the danger was imminent would most likely not have been enough. But as it turned out, we weren’t yet in danger’s way.

By Wednesday, the reports of loss started flowing in. The Pacific Palisades houses were burning like toast. I could see the smoke covering the hills as the bright red fire peaked over the tops. Another fire had started near Pasadena, then one in the northern part of the Valley, and so it went.

My building was about a mile and then less away from the evacuation zones in Santa Monica. I began to think about what to bring if we had to leave. My cousins’ homes were closer, and I checked in with them, offering them a place to sleep. Although how staying a half mile further away might be reassuring was not clear.

In the midafternoon a relative called to warn me that my two sons’ houses were near a new burn in the Hollywood Hills. The Sunset Fire. And that’s when my body began to shake. Ah, yes, the difference between a cognitive and a body experience. Sure, I was upset about all the houses, the people I knew or knew of who were losing everything. Sure, I was anxious about where else the fire would go. But my kids, their homes full of all our pre-digital family photo albums, full of hard drives of film footage, full of pets and guests and paintings and and and and. The boys, men, were both out of town. But there were people in the houses.

I got hold of them, one right away, the other after leaving texts and increasingly frantic voice messages. Their guests did evacuate, pets and all. That particular fire was contained within less than a day. But I got it. That body feeling was the signal. I knew it from earlier times in my life. From moments when I needed to make good decisions, or when decisions wouldn’t change the reality of something terrible happening. I knew it. We, all of L.A. knew or now know that experience. When life is out of control. When forces so much more monumental than our tiny wish to be in charge, to save each other, to make a difference, have reminded us of the truth of the situation.

The Buddhists are so wise in intoning, ‘All paths have pleasure and pain.’ Or ‘Life is like a river, always moving, always changing.’ We can’t avoid the pain. We can’t hold on to the pleasure. Our work is to detach enough to watch the changes come and go. Anicca, anicca, as my meditation teacher used to chant over and over. Impermanence, change, change.

Yes, L.A. will survive. It is a city familiar with the monumental upheavals of nature. Earthquakes, fires, mudslides, floods. Charred hillsides overnight turn to green grasses swaying in the wind when the rain finally falls. Roads closed and covered with mud are cleared, and convertibles race by in the bright sunshine. Freeways tumbled by earthquake, are rebuilt and flooded anew with endless lanes of cars. Angelenos are tough — we will join together to find our way.

And I will remember the feeling in the body that tells me that I am one small creature in a world of many. And that nothing is to be taken for granted. My little family has been beyond fortunate this time, but no one is exempt. If I am offered a momentary gift in between the moments of challenge, allow me to taste its sweetness, and remember the coming and going-ness of it all. I’m not in charge of that department. None of us is.

I fly to New England from Barcelona bursting with satisfaction. And in Massachusetts the fall foliage meets me in full voice. The reds and oranges and yellows crowding my already chock-full larder of happiness.

I fly to New England from Barcelona bursting with satisfaction. And in Massachusetts the fall foliage meets me in full voice. The reds and oranges and yellows crowding my already chock-full larder of happiness.

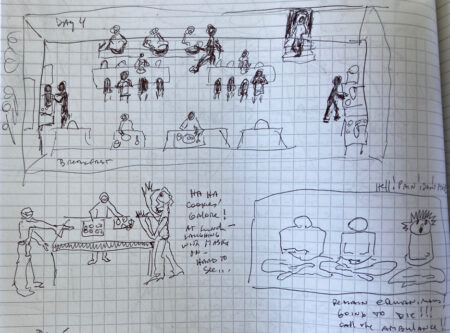

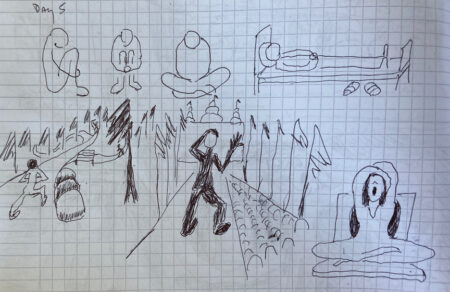

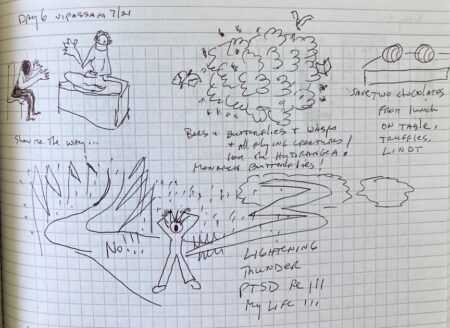

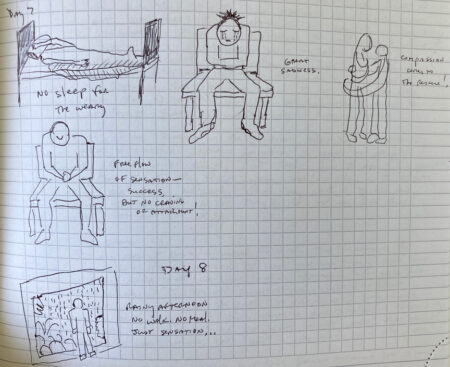

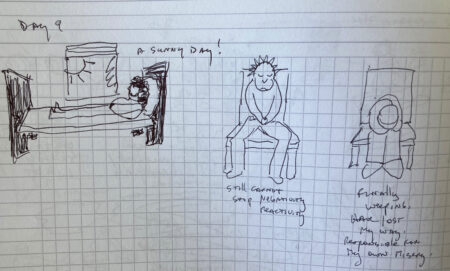

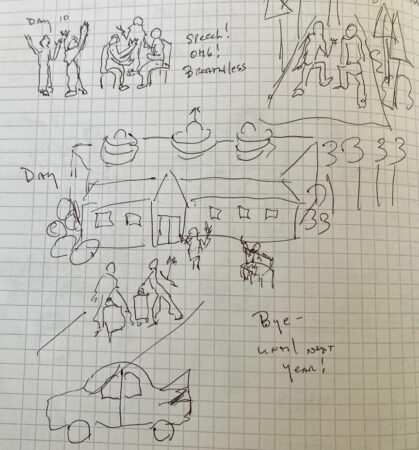

I recently attended a ten day silent meditation retreat in Shelburne Falls, MA. This was my fourth ten day there, but I’ve been at shorter ones in Shelburne and several long ones at Insight Meditation Society at various locations in the U.S. What I’m saying is that I’m no novice, no virgin, no innocent. The Shelburne Vipassana Meditation Center is reputed to be the ‘boot camp’ of retreats. Meaning, not for the faint of heart. I can attest to that.

I recently attended a ten day silent meditation retreat in Shelburne Falls, MA. This was my fourth ten day there, but I’ve been at shorter ones in Shelburne and several long ones at Insight Meditation Society at various locations in the U.S. What I’m saying is that I’m no novice, no virgin, no innocent. The Shelburne Vipassana Meditation Center is reputed to be the ‘boot camp’ of retreats. Meaning, not for the faint of heart. I can attest to that.

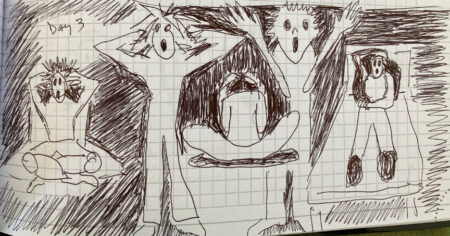

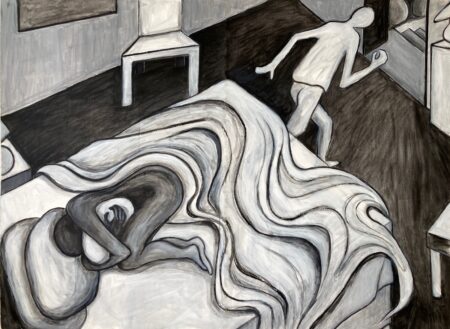

I suppose everyone has those times. And I have no idea why they occur when they do or even why they happen at all.

I suppose everyone has those times. And I have no idea why they occur when they do or even why they happen at all.