I recently attended a ten day silent meditation retreat in Shelburne Falls, MA. This was my fourth ten day there, but I’ve been at shorter ones in Shelburne and several long ones at Insight Meditation Society at various locations in the U.S. What I’m saying is that I’m no novice, no virgin, no innocent. The Shelburne Vipassana Meditation Center is reputed to be the ‘boot camp’ of retreats. Meaning, not for the faint of heart. I can attest to that.

I recently attended a ten day silent meditation retreat in Shelburne Falls, MA. This was my fourth ten day there, but I’ve been at shorter ones in Shelburne and several long ones at Insight Meditation Society at various locations in the U.S. What I’m saying is that I’m no novice, no virgin, no innocent. The Shelburne Vipassana Meditation Center is reputed to be the ‘boot camp’ of retreats. Meaning, not for the faint of heart. I can attest to that.

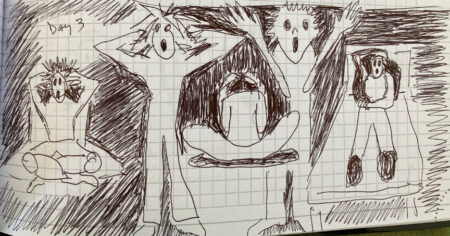

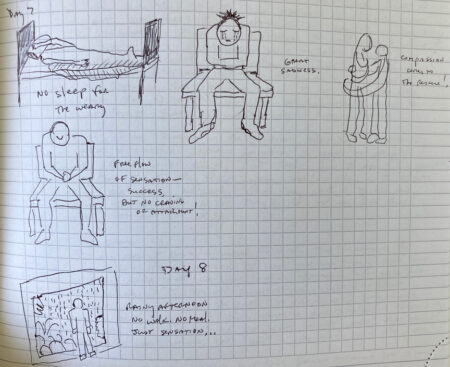

My very first time, maybe 1980 something or 1990, can’t remember the exact year, I learned a piece of information that would benefit me the rest of my life — a metaphor of sorts. As instructed, I sat without moving for an hour at a time over and over and noted every excruciating pain that I was convinced would result in lifelong dire consequences — my legs in the lotus position falling asleep, say, and my worrying that I was doing serious damage, or my back screaming in unbearable agony. I waited, didn’t budge, stalwartly sat on, until one, two, ten minutes later the feeling, each feeling, lifted of its own accord. The legs came back to life, my back simply stopped aching. A miracle. Miracle of miracles, as Tevye says in Fiddler on the Roof.

And the metaphor? You got it — when in pain just wait. Sit and wait. Don’t change position to avoid it or stop it. Just notice and be patient and it will pass. There will be new sensations, but they too will pass away. Both the pain and, alas, the pleasure arise and pass away.

It is a gift to experience the truth of this in the body. And later to watch the same truth evidence in the mind. Wow! Feel abandoned? Wait a while. Feel hurt by a friend? Just hang in and do nothing. No more calling a lover or pal in a panic. No more grabbing a glass of wine, a cigarette and that sad, sad Leonard Cohen album. Now I just settle in for the ride and work at remaining ‘equanimous.’ Okay.

But this retreat, thirty some years later, offers a different sort of revelation. Everything is the same in some respects — the teacher’s voice coming out of speakers, his explanations and directions identical to all the other times, but I am different. I’m so much older now, to bastardize the Dylan lyric, and, it turns out, I hear the whole thing, the lessons, with new ears.

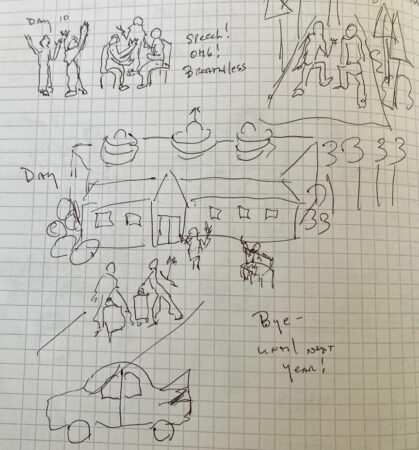

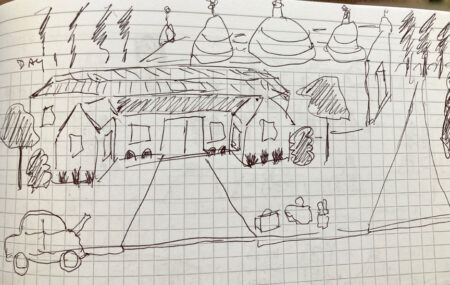

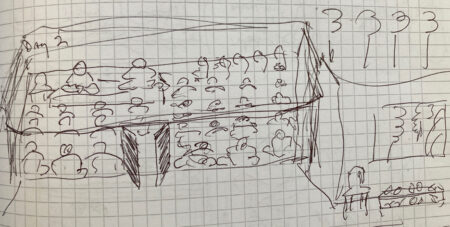

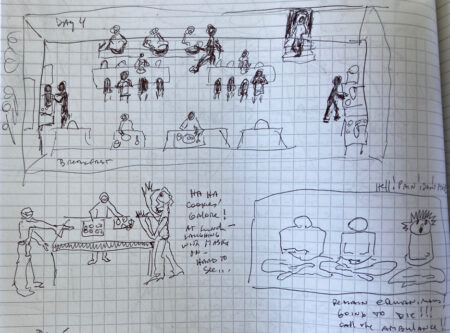

The day is spent sitting in a meditation hall with 80 others, eyes closed, not moving, a room so silent that the proverbial pin can be heard dropping on the floor. The silence is broken only for instruction on audiotape at the beginning and end of each hour. The technique is taught in a specific sequence: the first three days one focuses on the feeling of breath in the nostrils and on the upper lip, then the following seven days one learns Vipassana, the awareness of sensations throughout the body. We, the students, eagerly anticipate the short breaks to go to the bathroom, or outside for a walk, or to a meal — there are only two vegetarian servings allowed before noontime for ‘old students.’

It’s hard, grueling work, repetitive, unsurprising, mind numbing. But in the evening, after dinner, there’s a discourse by the teacher, the old, now dead, Burmese/Indian founder of Vipassana, S. N. Goenka. The discourse is a talk on video that explains the theory, or maybe it’s the philosophy, of the Buddhists, or specifically this teacher’s interpretation. And these evening discourses turn out to offer, on this particular retreat, the food for which I am hungry.

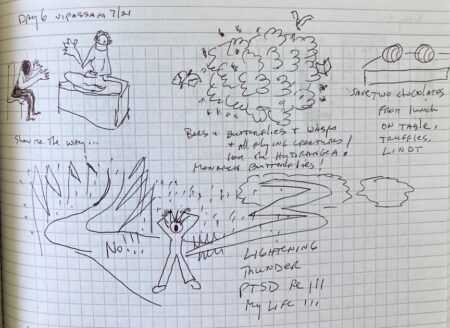

Goenka uses the ancient language of Pali to describe the three elements of meditation, and speaks of the movement towards enlightenment, whatever that truly is. But I understand the three elements — Sila, morality, Samadhi, concentration, and Paññā, wisdom. I am soothed by the emphasis on morality, a balm at this time of rampant corruption and dishonesty in our political, social, and even personal worlds. And I appreciate that the underpinning for reaching wisdom is experiential rather than intellectual. As we meditate we learn the truth and the art of living.

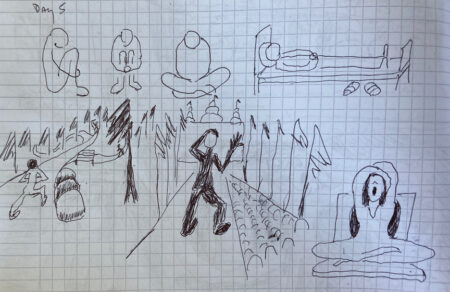

I am taken with the idea of impermanence. Like the water flowing in a river, change is a given in life. As we sit in the meditation hall, the teacher, repeats, Anicca, Anicca, meaning change, changing. It is a reassurance and a sorrow. When we are suffering, the promise of change is a godsend… my leg falls asleep but it will come back awake no matter what I do. When we are happy, the promise of change is a loss. Nothing stays the same. Craving the pleasure, feeling aversion for the pain, does nothing to change reality as it is. A blessing and a curse.

The bottom line, the goal, I am taught, is equanimity. Only by acceptance of things as they are can I live a life of peace. So easy to say, so difficult to practice. Am I sanguine when my knee is killing me but I hold it in position for an hour? Am I okay with the monumental suffering of the poor, the sick, the abandoned? What about the shocking inequity so glaring in L.A., my new home? I understand that even with injustice one needs to start from inner equanimity to be of use, that rage and fury do not lead to constructive action. But the road is not an easy one, neither facing the universal suffering surrounding me at this moment, nor the personal challenges that arise in each of our lives.

I sit and listen, then sit and experience. Then I sit some more. I finish the hour by offering Metta, good will, compassion, caring to others, but I wonder if this can in any way be enough. Then I sit again, and know it is simply what I am doing at this very instant, and that is the truth. I can only be here, now, here, now. In pain. In pleasure. In reality. As it is.